Many Names, One Ecosystem? Deciphering the Different Terms for the Second Renaissance Movement

In recent years, we have been observing the emergence of a global network of people and organisations who are acting to catalyse, steward and accelerate what we have called a "Second Renaissance": a major civilisational transition from modernity to a new cultural paradigm. We refer to this growing network as the "Second Renaissance movement" or "Second Renaissance ecosystem".

However, we recognise that the ecosystem's identity is far from singular or clearly defined. Moreover, while those whom we would consider to be part of the Second Renaissance movement tend to resonate with and be motivated by a particular high-level meta-narrative,1 there can be significant divergence in terms of values, diagnoses, aims, approaches, etc., once things get more specific.

Some of this diversity is reflected in the language that tends to be used across different parts of the ecosystem, or in different contexts. Specifically, groups and individuals within the space are currently using a range of names and terms to refer to:

- the period of civilisational transition we inhabit, or defining features of it (e.g., Great Turning, Second Renaissance, Metacrisis, Polycrisis)

- the new paradigm or approach that is emerging (e.g., Metamodern, Integral, Regenerative, Game B, Ecological Civilisation)

- the ecosystem or movement itself (e.g., Liminal Web, Sensemaking Web, Emergentsia, Holomovement)

While some of these names and terms are sometimes used interchangeably, the relationships between them are unclear. It remains an open question to what extent they point to the same ecosystem, emerging paradigm or historical diagnosis. For example, do certain terms point to sub-parts or communities within the larger space? Do certain terms refer to similar, but adjacent movements or concepts?

In this post, we provide an overview of some of the most widely used names and terms. It is intended as a resource to learn more about each one – its meaning, history, and the thinkers, perspectives and communities that tend to be associated with it. As we add more information over time, we hope that it will contribute towards a deeper understanding of the areas of overlap and divergence within the Second Renaissance ecosystem.

Second Renaissance

The “Second Renaissance” refers to a major civilisational transition that is currently underway: from the paradigm of modernity, which is breaking down, into what comes next. The Second Renaissance is a time between worlds – a period of civilisational crisis and awakening. In our introduction to the Second Renaissance, we articulate four core premises of what we see as the underlying meta-narrative:

- Real risk: There is a real risk of civilisational collapse and large-scale destruction of life due to intertwined ecological, political, social, and meaning crises.

- Root cause: The root cause of these crises lies in the cultural paradigm of modernity: in entrenched individual and collective ways of being, which are conditioned by modernity’s logic and values.

- Radical response: We are unable to address current crises through the logic and value systems that created and continue to drive them. We need responses that are radical in the etymological sense of going to the roots. That is, we need profound shifts in our ways of being, thinking, feeling, and acting: a new cultural paradigm.

- Real possibility: A transformation of cultural paradigm is possible and is already starting to happen.

The term “Renaissance”, meaning “rebirth”, is a reference to the 'first' Renaissance: the historical period and cultural movement of the 15th and 16th centuries in Europe, which marked the transition from the Middle Ages to early modernity. Like the First Renaissance, we see the Second Renaissance as a period of cultural and societal rebirth, characterised by a profound shift at the civilisational level in our most foundational views and values, such as:

- how we see ourselves and our nature as human beings

- how we approach the relationship between ourselves and the world around us

- what we think is meaningful and important

- our ways of knowing and learning about the world

The term "Second Renaissance" was first used by Francisco Varela in his book Ethical Knowhow: Action, Wisdom, and Cognition, published in 1999. He wrote:

"[…] it is my contention that the rediscovery of Asian philosophy, particularly of the Buddhist tradition, is a second renaissance in the cultural history of the West."

Further resources

- The Second Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction

- Why "Second Renaissance"?

- Ethical Knowhow: Action, Wisdom, and Cognition – Fransisco Varela

- A Time Between Worlds, Zak Stein

- Genesis in Three Performances - Sylvie Barbier

Metamodern

Broadly speaking, 'metamodern' is a term used to articulate developments in contemporary culture and society which are said to represent a move beyond modernism and postmodernism. It was originally coined in 1975 by Mas’ud Zavarzade, to describe an emerging cultural trend in American literature. 1 More recently, the related term 'metamodernism' has come into popular usage – although it has been defined and tends to be used in a number of different ways, which can make it rather confusing. Depending on the context, metamodernism is a philosophy; a worldview; a cultural sensibility; and a political, scientific, and social movement.

As a cultural and artistic sensibility, metamodernism is characterised by an oscillation between typically modernist attitudes and postmodernist ones – defined by its “ironic sincerity,” “pragmatic idealism,” and “informed naiveté”. The use of the prefix 'meta' derives from Plato’s metaxis, describing an "in-betweeness", an oscillation between diametrically opposed poles of experience. This usage was first proposed by Dutch cultural theorists Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker in their 2010 essay, “Notes on Metamodernism”.2

In The Listening Society and Nordic Ideology, Hanzi Freinacht articulates a political vision and program that has come to be known as 'political metamodernism'. In the books, metamodernism is presented as a philosophy and view of life (or what some call a "cultural paradigm", "cultural logic" or "cultural code") that corresponds to the digitalised, post-industrial, global age. Its key characteristic is the combination of the modern faith in progress with the postmodern critique. This gives rise to a worldview in which "people are on a long, complex developmental journey towards greater complexity and existential depth."3

Further resources

- What is Metamodernism?

- Metamodernism: A Brief Introduction

- Metamodernisms: A Cheat Sheet

- Metamodernism: A Literature List - Brent Cooper

- What is Political Metamodernism?

- The Listening Society - A Metamodern Guide to Politics, Book One - Hanzi Freinacht

- Nordic Ideology: A Metamodern Guide to Politics, Book Two - Hanzi Freinacht

- Metamodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Cultural Logics - Brendan Graham Dempsey

- Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds: Crisis and emergence in metamodernity

Metacrisis

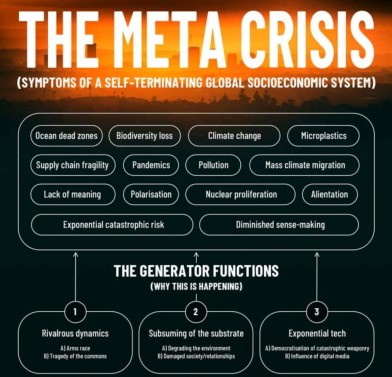

In simple terms, the metacrisis is the underlying crisis that drives a multitude of major, interconnected global crises, and gives rise to the various catastrophic and existential risks that we are facing as a civilisation.1 The term has gained significant traction within the Second Renaissance ecosystem, primarily through thinkers such as Jonathan Rowson, Daniel Schmachtenberger, Terry Patten and Zak Stein. The prefix 'meta' means after, between, within, beyond, more comprehensive, or transcending. Reflecting the many meanings of 'meta', there are also many meanings, definitions and attempts to unpack the metacrisis as a concept.

According to Daniel Schmachtenberger, the metacrisis is a frame for assessing the totality of risk that the world faces.2 There are thousands of (known) catastrophic and existential risks, which can only be expected to increase in likelihood and severity over the coming decades – all of which have to be prevented for our civilisation to "make it through". The metacrisis is a useful framing because it highlights the underlying patterns that give rise to these different crises and risks – providing a way to deal with them categorically, rather than trying to address each one individually. According to Schmachtenberger, coordination failures on collective action problems are the key drivers of the metacrisis. Addressing the metacrisis therefore requires fundamentally improving human coordination.

Other metacrisis thinkers locate the roots of the metacrisis deeper still. According to Jonathan Rowson, the metacrisis is an important idea because it highlights the interiority ('meta' as within) and relationality ('meta' as between) that are crucial, and often neglected, aspects of our predicament. In Rowson's framing, the metacrisis is fundamentally about our relationship to reality. He writes: "meta highlights that we also need to look within ourselves to psyche and soul, and also beyond, for a renewal in our worldview or cosmovision which has a direct bearing on prevailing ideologies and social imaginaries."3 Addressing the metacrisis necessitates better understanding "who and what we are, individually and collectively, in order to be able to fundamentally alter how we act."4 Playing with different interpretations of 'meta', Rowson identifies four main patterns of the metacrisis, as a way to highlight the impossibility of pinning it down to a single meaning.5 These patterns are:

- The socio-emotional meta/crisis (the crisis of 'we') – i.e., the difficulty of solving collective action problems, due to the limits of compassion and projective identification, and of not having a viable 'we' that can tackle them

- The educational metacrisis (the crisis of education) – see Zak Stein's definition below

- The epistemic meta-crisis (the crisis of understanding) – i.e., the problem of ideological and epistemic blind spots

- The spiritual meta crisis (the crisis of imagination) – i.e., being cut off from questions about the nature, meaning and purpose of life

In a similar vein, Zak Stein characterises the metacrisis as a "generalised educational crisis", which is fundamentally a crisis of the psyche – it is "in our minds and souls". He differentiates four aspects in which this manifests in how we respond to the crises and risks that are facing us:4

- A sense-making crisis ("What is the case?")

- A capability crisis ("How can it be done?")

- A legitimacy crisis ("Who should do it?")

- A meaning crisis ("Why do it?")

Further resources

- Metacrisis.org

- An Introduction to the Metacrisis - Daniel Schmachtenberger - Stockholm Impact Week 2023

- Tasting the Pickle: Ten flavours of meta-crisis and the appetite for a new civilisation - by Jonathan Rowson

- Prefixing the World - by Jonathan Rowson

- Google Talk – Confronting the Meta-Crisis: Criteria for Turning the Titanic - Terry Patten

- Education is the Metacrisis - Zak Stein

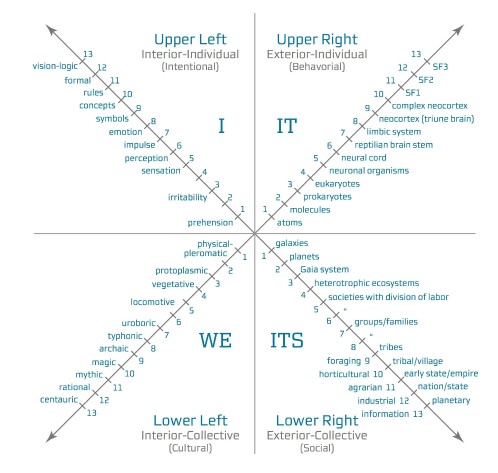

Integral

Integral theory is American philosopher Ken Wilber’s attempt to integrate all the known systems and models of human growth into a single, holistic, multidimensional framework for human evolution. An integrated or 'integral' approach to studying human potential seeks an integration of mind, body, and spirit; of material and spiritual values; and of Eastern and Western philosophies and worldviews. 1,2 The purpose of an integral approach or 'map' is to see oneself and the world in more comprehensive and effective ways. There are five essential elements of Integral Theory:3

- States (of consciousness): temporary modes or levels of awareness that individuals can experience (e.g. waking states, dreaming states, meditative states, flow states, altered states, and peak experiences).

- Levels (or 'stages' of consciousness development): permanent milestones of growth and development, representing increasingly higher levels of complexity or organisation.

- Lines (of development – or 'multiple intelligences'): domains or dimensions of intelligence along which people can develop (e.g. cognitive, emotional, kinesthetic, interpersonal, moral and self-identity).

- Types (masculine and feminine): a horizontal typology for different versions or dimensions of the same item, such as a stage of development.

- Quadrants (how all the other components fit together): four quadrants displaying the four dimensions of every event – the “I” (inside of the individual), the “it” (outside of the individual), the “we” (inside of the collective), and the “its” (outside of the collective).

Since integral theory was first introduced in 1977 with the publication of The Spectrum of Consciousness, a global community of meta-theorists and practitioners has evolved around it. The Second Renaissance ecosystem includes communities and organisations that make significant use of the integral framework, with the term "integral" being sometimes used to refer to the approach or paradigm that they are seeking to foster, as well as the ecosystem itself.

Further Resources

- What is the Integral Approach?

- Integral Spirituality - Ken Wilber

- Summary of Integral

- Institute for Integral Studies

- California Institute of Integral Studies

Polycrisis

The "polycrisis" is defined by the Cascade Institute as "any combination of three or more interacting systemic risks with the potential to cause a cascading, runaway failure of Earth’s natural and social systems that irreversibly and catastrophically degrades humanity’s prospects."1 Essentially, a polycrisis arises when multiple systems across various domains are in crisis simultaneously, and interact with each other to create a "complex and intertwined web of challenges.” 2

The term was coined in the 1999 book Homeland Earth: A Manifesto for a New Millennium by Edgar Morin and Anne Brigitte Kern,3 and was recently popularised by historian Adam Tooze.4 "Polycrisis" has become a relatively mainstream term, particularly outside of the Second Renaissance ecosystem. For example, it has been used by the World Economic Forum, and it was chosen by the the Financial Times as the word to describe 2022.5 It is sometimes used interchangeably with the term 'metacrisis', although the two concepts are distinct.

Further resources

- What Is a Global Polycrisis? And how is it different from a systemic risk? - Cascade Institute report

- This is why 'polycrisis' is a useful way of looking at the world right now - World Economic Forum

- Explaining Polycrisis and Metacrisis

- Year in a word: Polycrisis

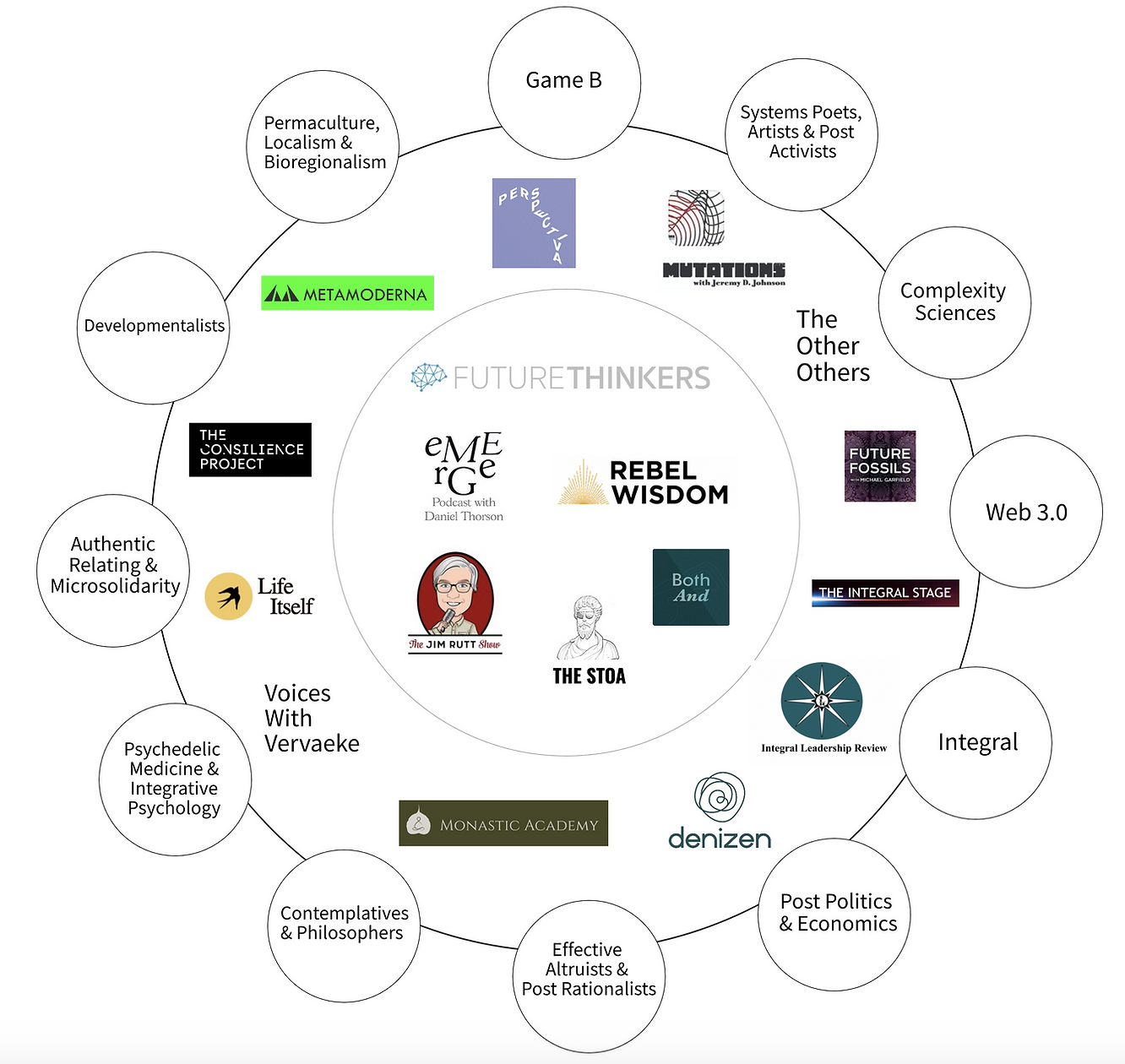

The Liminal Web

In 2021, Joe Lightfoot published a blog post attempting to map “an emergent subculture of sensemakers, meta-theorists & systems poets”, which he termed the “Liminal Web”:

”a collection of thinkers, writers, theorists, podcasters, videographers and community builders who all share a high crossover in their collection of perspectives on the world. It not only includes creators of content but also the people and communities who resonate with the constellation of ideas such creators put forward.” 1

'Liminal' means ‘to occupy a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary or threshold’. The choice of this word reflects the idea that "everyone in the space is in their own unique way attempting to mid-wife a new kind of regenerative culture whilst simultaneously hospicing the old".2 'The Liminal Web' has since become a popular term for referring to the emerging ecosystem.

Further resources

- The Liminal Web: Mapping An Emergent Subculture Of Sensemakers, Meta-Theorists & Systems Poets - Joe Lightfoot

- Metamodern Spirituality | The Liminal Web and Communitas (w/ Joe Lightfoot)

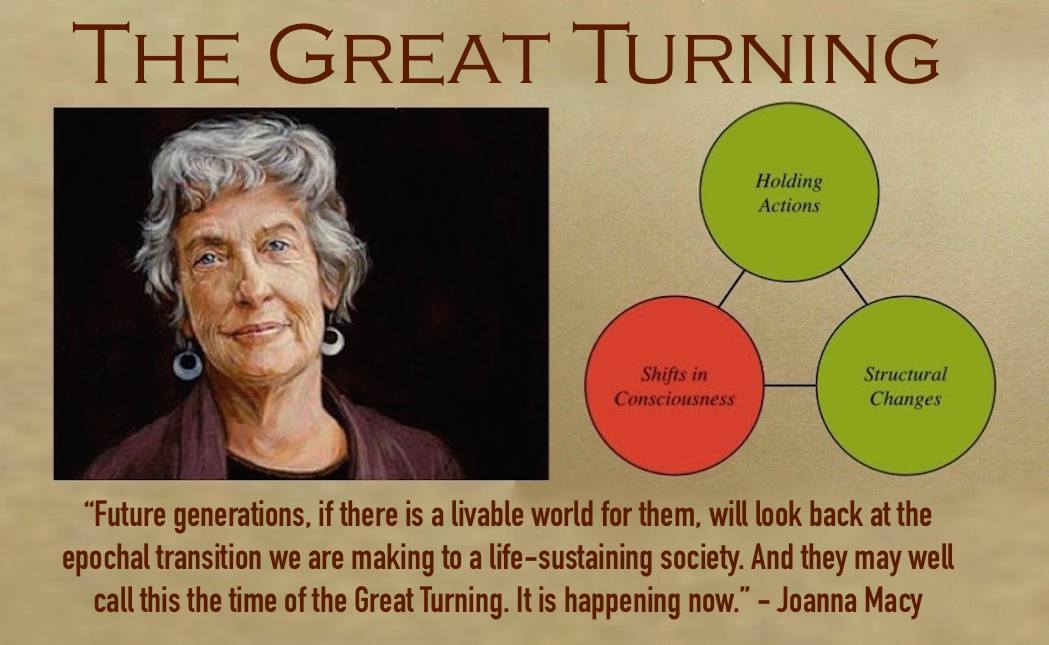

The Great Turning

The Great Turning, coined by Joanna Macy, is a shift from the Industrial Growth Society to a life-sustaining civilisation.1 Macy identifies three main narratives of our times: "Business as Usual", upholding the growth economy; "The Great Unraveling", telling the story of ongoing collapse of living structures; and "The Great Turning", which is a civilisational transition comparable to the agricultural and industrial revolutions.2 Macy urges us to recognise what is happening in the world today, and to align our work with the Great Turning and the creation of a life-sustaining civilisation.

According to Macy, there are three dimensions of the Great Turning – that is, three types of actions that are needed for the transition to occur:3

- Actions to slow the damage to Earth and its beings (aka "holding actions")

- Analysis of structural causes and the creation of structural alternatives (aka "structural changes")

- Shift in consciousness (i.e. a profound shift in our perception of reality, as well as in our values and norms)

Further resources

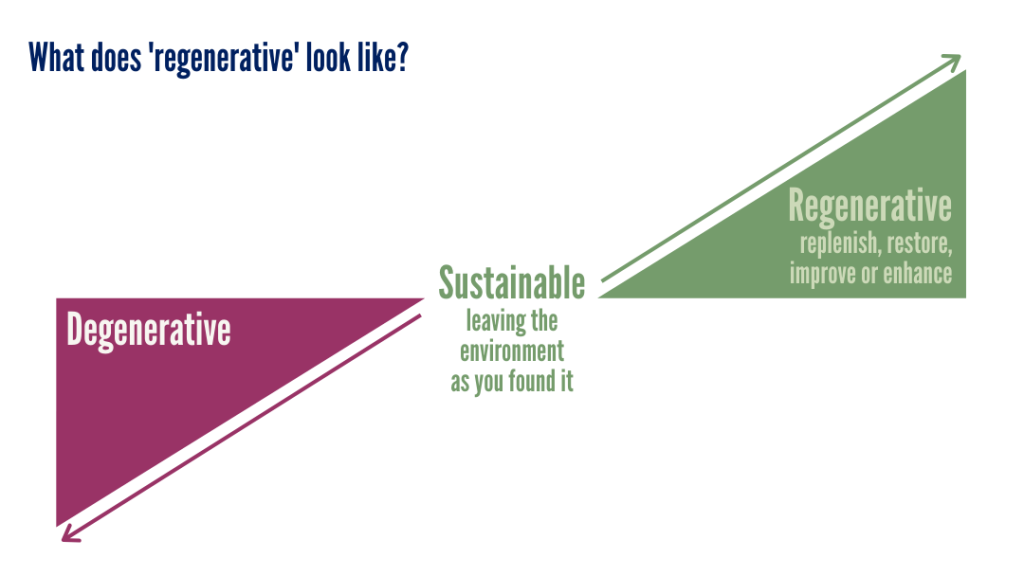

Regenerative

The concept of regeneration – and the social movement associated with it – can be contrasted with the more widely known concept of sustainability. While sustainability is about leaving the environment "as you found it" by seeking to neutralise negative impacts, regeneration is about replenishing, restoring, or enhancing – actively seeking to improve an ecosystem's resilience and capacity to regenerate. An example of regeneration is the restoration of Loess Plateau in China in 1994, where the Chinese government and the World Bank collaborated on restoring biodiversity and life-systems in nearly 4 million acres of over-grazed, over-harvested lands in north-central China.1

In recent years, a regenerative approach has been increasingly applied to the design of cultures and human systems. Key principles involve seeing ourselves as living in patterns of relationships, rather than as separate individuals; seeing these relationships as part of wider living systems; and seeing these patterns as constantly evolving and emerging processes.2

Further resources

- Designing Regenerative Cultures — Introduction

- Regenerative Cultures, with Daniel Christian Wahl

- The Design Pathway for Regenerating Earth - Joe Brewer

GameB

GameB is a sense-making community espousing a need for a collective shift from “Game A” (old paradigm) to a new kind of civilisation (“Game B”) that does not reproduce the rivalrous dynamics inherent in Game A which produce existential risk.1 It has also been described as "a transcontextual inquiry into a new social operating system for humanity"2, and tends to draw on evolutionary game theory for its theoretical framework and approach to systems change.

Proponents of Game B argue that any attempt to precisely define it would suffer from the reductionist tendencies of Game A. Instead, they tend to offer a number of different constructions that point to Game B (as well as a definition in terms of what Game B is not).3 For example, Game B has been characterised as (among other things):

- an "infinite game where the purpose is to continue playing" (vs. Game A being a "finite game where the purpose is to win");

- "building or developing the capacity to navigate complexity without resorting to complicated systems"; and

- "a new mode of societal, economic, and political organization that leverages people's authentic, long-term interests towards a healthier, more cooperative society and improved well-being"

Further resources

- GameB wiki

- GameB Home

- Future Thinkers podcast: What is GameB? - Jim Rutt

- Jim Rutt Show: EP26 Jordan Hall on the GameB Emergence

Ecological Civilisation

An ecological civilisation is one that uses the design principles of nature to reimagine itself – to change its 'operating system' so that it leads to "life-affirming policies and practices rather than rampant extraction and devastation".1 The term has been popularised by Jeremy Lent.

Further resources

- An Ecological Civilisation | Jeremy Lent

- How to Move Towards an Ecological Civilisation: With Jeremy Lent

- Institute for Ecological Civilisation

Emergentsia

"Emergentsia" is a term coined by Brent Cooper in 2019. It refers to "a new class of intellectuals [that] is emerging to grapple with the meta-crisis and help manage the transition".1

"The Emergentsia transcend and include the characteristics of an intelligentsia, at a higher level of emergence and planetary vision-logic. They are to emergence what the intelligentsia was to intelligence. They synthesize very complex conceptual frameworks and apply them to deep existential problems and solutions. This entails grappling with long-term and big-picture ideas that often take years of intense study to penetrate, let alone to be able to distil into accessible and actionable terms. The idea of the Emergentsia arose from noticing shared characteristics among thinkers like Daniel Schmachtenberger, Jordan Hall, Jamie Wheal, Jason Silva, Zak Stein, Bonnitta Roy, Maja Göpel, Indra Adnan, and Indy Johar, who are all active in the topics of emergence and systems change."2

Further resources

Teal

'Teal' is a term that derives from Spiral Dynamics, a model of the evolutionary development of individuals, organisations, and societies developed in the 1960s and 70s by Clare Graves, Don Beck and Chris Cowan.1 Stages of development, or 'value systems' in the Spiral Dynamics framework are coded with colours, with 'teal' or 'turquoise' being the final of the currently known stages. Several variations of Spiral Dynamics exist that have been incorporated into, or that draw on, Ken Wilber's Integral theory.2 Within the Second Renaissance ecosystem, 'teal' is sometimes used as a term to refer to the emerging paradigm or approach, and often as a synonym for 'metamodern' or 'integral'.

Further resources

Sensemaking Web

The 'Sensemaking Web' (or 'Sensemaking Scene') is a largely synonymous term for the Liminal Web. It highlights the shared goal of those within the space to 'make sense' of the world.

Further resources

Holomovement

.jpg)

The Holomovement is "a social movement that awakens us to our interconnectedness, igniting a critical mass of collaborative action serving the good of the whole."1

"Guided by science and spirituality, this unifying movement is catalyzing a massive shift in human consciousness."